The primary focus of Sean’s practice three main components. The first is based on the use of recycled material, focusing on themes of displacement and sustainability. A number of exhibitions were cobbled together using discarded materials from housing renovations, garage demolitions and construction off-cuts. The second compliments this work and are photographic studies examining human traces in nature and the documentation of Urban Forest Remnants, the remains of the forest mentioned above. The third is his work with Public Commissions as both artist and facilitator. The most recent project in this area has been a heritage project for the City of Regina to replace the twelve missing frog spitters in Regina’s Confederation Park, which was realized by collaborating and working with four very talented students. Increasingly, this last element of Sean’s work has crossed over with his teaching practice where making and teaching have become interactive collaborative experiences.

While working at the Black Creek Historical Village in North York, Ontario, I came across several references to early settler’s farming practices when Europeans first made the journey to “North America” . When they first arrived, they encountered a broadleaf forest so vast it stretched from (roughly) Barrie, Ontario to Mississippi uninterrupted. The old growth trees in this forest were so large settlers were unable to cut them down. As a result, to establish their farms and homesteads, the trees were girdled to kill their canopy.

Girdling is a process of removing a trees’ bark to the cambium in a ring around the tree’s circumference. This starves the tree’s canopy of nutrients by disrupting the flow of nutrients from the roots. Without leaves, the farmers were free to plant their food crops around the trees. The irony of this practice is that the once rich soil soon became exhausted because of its disrupted cycle (the trees no longer dropped leaves to fertilize the soil) and the settlers began to move slowly along clearing the forest as they moved.

While growing up in Southern Ontario, I encountered a few remnants of this old growth forest, scattered throughout suburban areas, cemeteries and little-known hidden parks and reserves. During several summers I returned to many of these remnants to document them. Some of the trees are over 500 years old, some are second growth and are between 200 and 300 years old. The largest, oldest and most famous tree in this series is known as the Comfort Maple, has a girth of twenty-one feet and is over 550 years old.

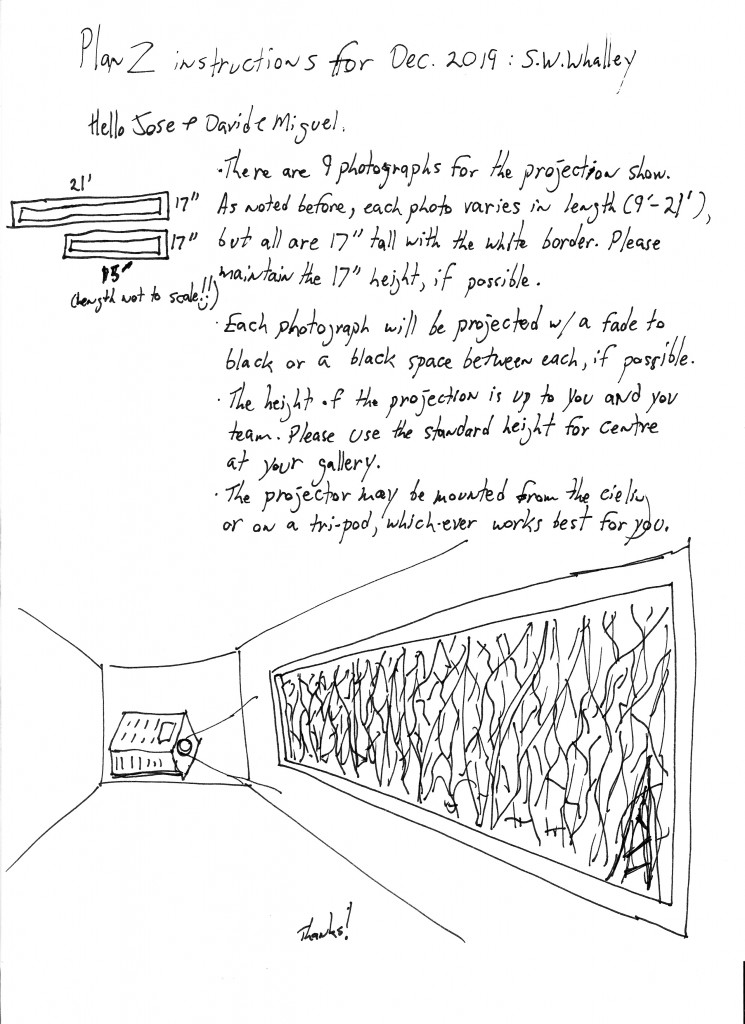

The intent of capturing the “girth” of the tree and printing panoramic photographs in seventeen-inch-wide strips is to acknowledge and partly reclaim that lost space, that lost history and the lost heritage of that broad leaf forest with the hopes of allowing these gentle giants to have a voice.